“Jazz just kind of died,” said the saxophonist Branford Marsalis. “It just kind of went away for a while.” He was looking back to the 1970s, an uncertain era when some jazz musicians turned to rock or funk, and others pushed deeper into heady abstraction. His assessment, conveyed in the final episode of “Jazz,” the influential Ken Burns film, seemed as definitive as a coffin nail.

But over the last six months, a far-flung contingent of musicians and aficionados has made an effort to upend that prevailing notion, armed with stacks of vinyl, high-speed Internet and a shared conviction that things back then were really far from moribund. Along the way, they touched off the year’s most animated public discourse on jazz, a democratic exchange that culminated last weekend in the debut of behearer.com, an interactive database devoted to the music’s most conflicted period.

The movement, so to speak, has its origins in a posting by the trumpeter and composer Dave Douglas on his label’s blog, greenleafmusic.com. “I’m reading a new book by Philip Jenkins called ‘Decade of Nightmares: The End of the Sixties and the Making of Eighties America,’ ” Mr. Douglas wrote at the beginning of the summer, “and I think there are some pertinent tie-ins to the elusive history of the last four decades of American music. Those are the decades Ken Burns couldn’t handle, and this may help explain why.”

That book’s principal argument is that the 1970s saw the failures and excesses of ’60s idealism compounded by national horrors like Vietnam and Watergate, resulting in the rise of a paranoid conservatism. On his blog Mr. Douglas drew a parallel. “There’s a demonization of musicians who pushed the boundaries, successfully and importantly, in that period,” he wrote, “and it has crept into the way history is told and music is taught.”

Noting that “jazz” became an impossibly broad designation around this time, Mr. Douglas posed a rhetorical question: “Is there a writer who can take on the project of an unbiased overview of music since the end of the Vietnam War?” And borrowing Mr. Jenkins’s benchmark of Richard M. Nixon’s resignation as the official end of the 1960s, he proposed a new jazz history that would acknowledge “a generation of multiplicity,” beginning in 1974 and stretching to the end of the cold war.

The call hung in the air for a while. Then, near summer’s end, a reply of sorts appeared on Do the Math, the blog of the band Bad Plus (thebadplus.typepad.com/dothemath). Ethan Iverson, the pianist in the band and the chief blogger on the site, answered Mr. Douglas’s query not with an unbiased overview, but a catalog of hundreds of cherished albums from his collection, complete with casual but articulate annotations.

Mr. Iverson was transparently subjective (“Every note is perfect,” he wrote of Charlie Haden’s out-of-print LP “The Golden Number”) and often pithy (“If you don’t like ‘The Calling,’ I can’t help you,” he said about a track from Pat Metheny’s album “Rejoicing,” also featuring Mr. Haden).

“I could have made this list much longer,” he wrote in conclusion, “but how many Paul Bley and Mal Waldron records can you put on a list without looking silly?” All told, Mr. Iverson had churned out nearly 5,000 words.

Within a couple of days, Do the Math was so bombarded with feedback that Mr. Iverson set up a temporary e-mail address and announced a one-week call for outside submissions. By the end of that week there was not only a blizzard of e-mail messages from around the world but also a handful of lengthy responses from every corner of a nascent jazz blogosphere.

Darcy James Argue, the leader of a big band called the Secret Society, posted his own expansive list at secretsociety.typepad.com. Steve Smith, the classical editor at Time Out New York and a contributor to The New York Times, spilled even more words than Mr. Iverson at nightafternight.blogs.com, beginning with an erudite endorsement of John Carter, an overlooked composer. Jeff Jackson (blog name: Chilly Jay Chill) and Jeff Golick (Prof. Drew LeDrew), proprietors of destination-out.com, piped up in favor of the pianist Muhal Richard Abrams and the saxophonist Marion Brown.

The resulting list of nearly 500 albums — compiled by a Boston-based saxophonist named Pat Donaher at visionsong.blogspot.com — is essentially the product of an open-source, alternative canon-building sweep. Though idiosyncratic and avant-garde in temperament, it feels admirably nondogmatic. Fusion flagships (Weather Report, Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra) are selectively represented, as are acoustic efforts by veterans like Tommy Flanagan and Joe Henderson. Because the timeline stretches through the 1980s, Wynton and Branford Marsalis both make the list.

[snip]Of course the jazz blogosphere is not a modern facsimile of the United Hot Clubs. Yet the free MP3’s featured at destination-out.com, usually grafted from out-of-print LPs and posted with chirpy yet incisive analysis, do serve a similar purpose: “to give this essential music its due and share it with folks so they can hear for themselves,” as Mr. Jackson wrote in a recent e-mail message.

Behearer.com, named after a Dewey Redman album and assembled over the last two months by a handful of volunteers, shares that impulse of openness. The charge has been led by a programmer, Brett Porter (bgporter.net). At the moment it’s not much more than a cross-indexed list of recordings, starting with the blog-consensus catalog. But because the site has the same sort of user-editing functionality as Wikipedia, it has the potential to evolve into a clearinghouse. What’s needed is the continuing engagement of a community online.

Mr. Douglas has faith in that community, which has supported Greenleaf Music since it was established last year. This week the label will record his working quintet at the Jazz Standard; each set will be offered as a $7 download within 24 hours at musicstem.com. In some ways this arrangement recalls the rugged self-reliance of the 1970s avant-garde, but with better technology and a savvier business plan.

It also underscores a point about the jazz blogosphere: no matter how retrospective the discussion, virtually all of the participants have a stake in the contemporary scene. So their interconnectivity has implications beyond the scope of history; you could even make the Marsalisesque argument that by preserving the past, their efforts help secure the music’s future. Many overlapping versions of the future, to be precise.

.

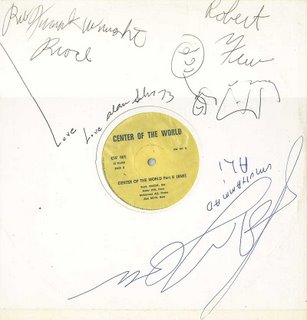

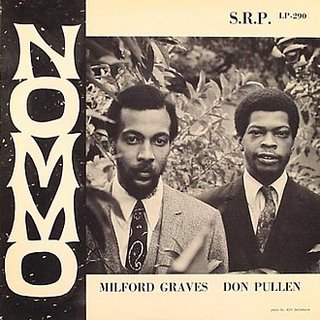

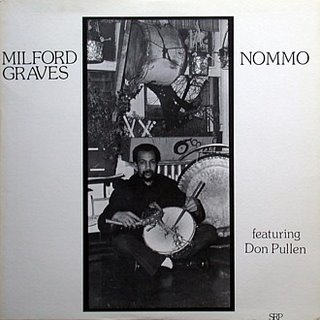

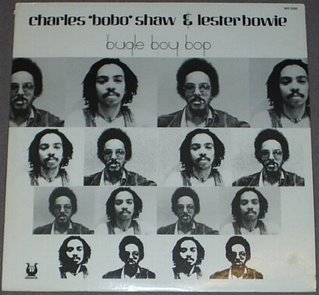

A personal favorite for a number of years, that I tracked down on ebay (and which will often fetch a premium unless you get lucky, which was what happened in my case).

A personal favorite for a number of years, that I tracked down on ebay (and which will often fetch a premium unless you get lucky, which was what happened in my case).